In 1996, banker Elouise Cobell became the lead plaintiff in a class action suit, demanding back payment and better accounting on Individual Indian Money Accounts managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Thirteen years later, the federal government settled for $3.4 billion, the largest settlement in U.S. history.

Elouise Cobell

By Bethany R. Berger

“We never asked for this system; it was imposed on us. Now, they are mismanaging our money–not appropriations or donations, but our own money–and we can’t fire them. All that’s going to change. We are not going to let them off the hook. There has to be reform and restitution. There has to be justice.”1

Elouise Cobell grew up hearing her relatives tell the story of Ghost Ridge. The rising near her uncle’s house on the Blackfeet Reservation was a mass grave for over 500 Blackfeet who died of starvation and disease in the Starvation Winter of 1883 and 1884. Although the United States Government was supposed to provide rations under its treaties with the Blackfeet Nation, the local federal agent hoarded the rations to sell on the black market.

Driven by such stories, Cobell spent her life seeking accountability for government abuse of Indian property and restoring Indian control of their financial futures. Before she died in 2011, she had founded the first Native American bank, won a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, been honored as a warrior by her tribe, and made the United States to agree to pay 3.4 billion dollars—the largest federal class action settlement ever made–for its mismanagement of Indian property.

Elouise Cobell was born on the Blackfeet Reservation in 1945, the middle of nine children. Her parents had a small ranch, and like many reservation families at the time, they didn’t have electricity or running water. Life wasn’t easy; three of her siblings didn’t survive childhood. Cobell described herself as a bashful child, and throughout her life those who met her were surprised at her quiet, soft-spoken demeanor. But she was the great-granddaughter of Mountain Chief, who had led his people first on the battlefield and then in negotiations in Washington, D.C. Her parents raised her to be a strong woman, and, like Mountain Chief, her determination took her to D.C. to fight for her people.

When Cobell was four years old, her father managed to get a one-room schoolhouse built so local children would not have to go away to boarding school. She recalled visiting the new school with her father, sitting down, and refusing to leave until she could attend. She went to school there until leaving for high school fifty miles away. That one room exposed her to the world outside the reservation. “It opened my eyes and made me want to do a lot of things.”

As a child, Cobell often heard her parents and their friends complaining about Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) management of their land. Like hundreds of thousands of Indians across the country, they owned rights to lands held in trust by the federal government. The BIA leased the land on their behalf, and was supposed to give them checks for the proceeds. Some trust land had valuable oil deposits or timber, other land supported profitable farms. But some years the checks came, and sometimes they didn’t, and they were for tiny amounts that varied without explanation. Good with numbers, and trying to understand the poverty she saw around her, Cobell starting asking the BIA for an accounting of her trust monies when she was just 18. The officials refused, telling her she wasn’t “capable” of understanding it. The refusal just spurred her on. “If someone tells me something can’t be done, I get so mad I just have to do it,”2 she said.

Cobell first studied accounting at Great Falls Commercial College, then went on to study business at Montana State University. While in college, she interned as a clerk at the reservation BIA office as part of a work study program. There, she saw many others dismissed when they came to ask about their trust accounts. “People would come in and try to get information, and they’d just make them sit out in hard, old wooden chairs. I had no idea at that point that it was their own money.”3

Cobell left college in her junior year to take care of her mother, who was dying of cancer. “She begged me to please stay in school,” Cobell recalled, but she thought, “I can go to school anytime.”4 She never did go back. After her mother’s death, she left for Seattle, where she worked in the accounting department of a local television station. There, she met and married her husband, Alvin Cobell, another Blackfeet working in Washington, and had a son, Turk Cobell.

The family returned to the reservation in 1971 when her father asked them to come home to help with the family ranch. Her brother had become paralyzed, and the ranch had fallen into debt. “Once we got on that ranch,” Cobell recalled, “there was no going back. We just wanted to make sure we held on to our land, that nobody would take it from us.”5 Although she would wear many hats, Cobell remained a rancher for the rest of her life. She helped her husband put out hay for the cattle in the winter, and care for baby calves in the spring. One reporter recalled her returning home in her light blue business suit and walking through the mud to round up two cows that had escaped through a hole in the fence.6

In 1976, the Blackfeet Nation asked Cobell to become treasurer for the tribe. There, she clashed again with the BIA when she asked about the tribe’s assets. She wanted to know why, when trustees are supposed to place trust assets in safe, profitable investments, the tribe was receiving negative interest checks. The officials told her she should learn to read a financial statement. Humiliated but undeterred, she kept tracking discrepancies and asking for explanations.

At the same time, Cobell battled to help tribes and individuals secure financing without relying on the BIA. In 1983, the only bank on the reservation closed, leaving residents with no bank within thirty miles. After attempts to persuade an existing bank to open a branch on the reservation failed, Cobell decided the Blackfeet Nation needed to open its own bank.

Reservation Indians often have trouble getting loans from traditional banks. Much reservation land is held in trust and cannot be seized as collateral. Traditional banks also are often unwilling to deal with the potential of tribal jurisdiction. The difficulty securing loans, Cobell thought, was a big obstacle to Indian success. A tribal bank could try to breach this gap.

In 1987, the Blackfeet National Bank opened its doors.7 It was the first bank in the country owned by an Indian tribe. When it opened, the bank had one million dollars in capital. In ten years, its assets multiplied to $17 million.8 In 2001, twenty tribes joined in the newly christened Native American Bank. Today, twenty-six tribes participate in the bank, which has assets of $82 million, and provides financing across Indian country.9

In 1997, the MacArthur Foundation awarded Cobell a grant of $310,000 in recognition of her work with the bank and for financial literacy. The awards are nicknamed “genius grants.”

Recalling the BIA officials who dismissed her questions about their accounts, Cobell later joked about having made the leap from “dumb Indian” to “genius” in one lifetime.10 Awardees don’t apply for the awards, they just get a phone call telling them they’ve won. On first hearing about the award, Cobell said, “I think I cried for three hours. It just felt like ‘Oh my God, somebody cares.’ Sometimes you get the feeling, especially in Indian country, that you’ll never get a win. Somebody is always on your case.”11 At the time, she said she was unsure what she wanted to do with the money, but had “three or four things, or maybe 20 things on my list. I’ll figure it out sometime. I want to do something fun, though.”12

Cobell never did get to do something fun with the money. Instead, the award was plowed into the project that would take the rest of her life: fixing BIA trust accounts.

***

The trust account problem began almost two hundred years ago. Tribes across the nation ceded billions of acres of land to the United States; in hundreds of treaties, the United States promised payment for the lands. After 1820, rather than distribute payment to the tribes directly, the U.S. held the money for the tribes. If a tribe won a money award for illegal taking of their property, the United States held that money as well. The U.S. made the decisions about investing the money, and if a tribe wanted to use it themselves, it had to get federal permission first.

Problems with the system began almost immediately. In 1828, federal agent and ethnographer Henry Schoolcraft wrote that it seemed that the Indian department’s fiscal affairs “had been handled with a pitchfork [T]here is a screw loose in the public machinery somewhere.”13 In 1992, a comprehensive congressional report concluded, “[o]ne hundred sixty- three years later, Schoolcraft’s assessment of the BIA’s financial management still rings true. . . [W]hile mismanagement of the Indian trust fund has been reported for more than a century, there is no evidence that either the Bureau or the Department of the Interior has undertaken any sustained or comprehensive effort to resolve glaring deficiencies.” 14

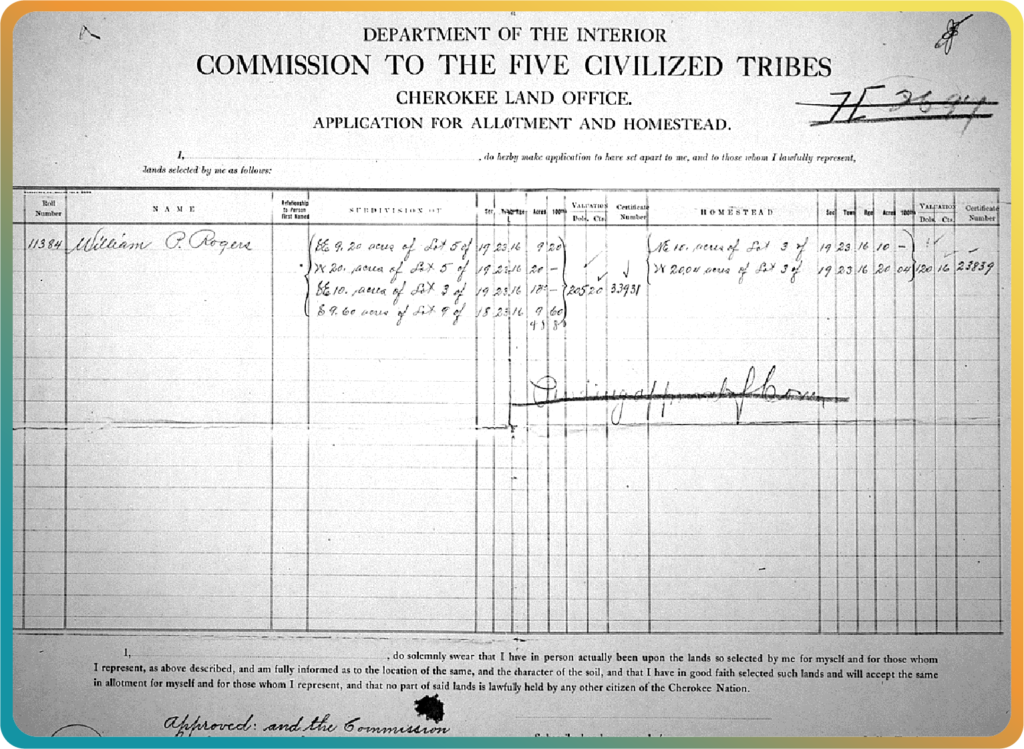

The problem increased exponentially as a result of the federal allotment policy. In the last part of the nineteenth century, the United States decided that individual ownership of land would convince Indians to abandon their tribes and their cultures, and thereby provide the magic cure for the “Indian problem.” Not coincidentally, the policy would also transfer most Indian land to whites. As formalized by the 1887 Dawes Allotment Act, commonly held reservations would be divided among individual Indians in allotments of up to 160 acres. The allotments would be held in trust for twenty-five years, and then could be sold by the Indian owner. Anything left over after allotment was declared “surplus,” and opened up to states, railroads, and homesteaders.

Allotment was a disaster. The majority of tribal land was declared surplus and lost to land- hungry whites. Once individual allotments were subject to sale, most of that was lost as well— sold to support poor families, stolen in fraudulent sales, or seized for back taxes or other debts. Indian farming—supposedly the goal of allotment—actually declined by a third.

In 1934, Congress forever terminated the policy of allotment. By then, ninety million acres, two-thirds of the 1887 tribal land base, was gone. Reservations were now checkerboards of Indian and non-Indian ownership, with much of the best land in non-Indian hands. Allotted land that was not yet subject to sale would forever remain in trust. The BIA, in other words, would have to consent to any sales, leases, timber harvesting, or mineral extraction. And the income from the land—some 11 million acres15—would be managed by the BIA itself.

Even worse, the number of individual allotment holders kept growing. Under the 1887 Allotment Act, allotments were subject to state probate law. Because few Indians—many of whom could not speak English, much less write—had written wills, this usually meant that property descended to the heirs determined by state intestacy laws. Although these laws vary from state to state, a typical distribution might include a man’s estate going in part to his wife and in part divided equally among his children; or, if there were no spouse or children, to his parents and siblings, or if the siblings had died, to their children. With each generation, the number of people with interests in an allotment would multiply. By 1934, rights to a single allotment might be divided among dozens of individuals, while individuals might have minute shares to 30 or 40 allotments.16 By 2004, some interests amounted to only .0000001 percent of an undivided allotment. This fractionation made it impossible for all of the owners to get together to manage the land themselves, and multiplied the difficulty for the BIA of figuring out who had what interest in the land.

Not that it seemed the BIA cared much about figuring it out. General Accounting Office reports in 1928, 1952, 1955, 1966, 1982, as well as other federal reports and audits by private accounting agencies, reported major problems with the BIA’s handling of tribal and individual trust accounts. In violation of federal law, the BIA failed often failed to invest money in interest bearing accounts, and failed to get compound interest when it did. There was no policy of telling or compensating account holders when the agency wrongly lost their money—officials just waited for the individual to complain.17 They even sometimes used the money in the accounts as a slush fund for other purposes. In one case, Cobell found, they loaned part of the Blackfeet fund to another tribe, and just forgot to replace it. But the reasons for the loans were sometime more exotic—according to Cobell, they included the New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis, a Chrysler bailout, and writing down part of the national debt.18

The most basic problem was failure to follow fundamental accounting procedures in recording and updating accounts. As a result, the BIA had little idea of what money came in, what should go out, or who should get it. Year after year, governmental auditors told the BIA to reconcile the accounts and institute basic procedures. Year after year, the BIA failed to do so, though it did spent millions of dollars on expensive private accounting programs that could not work because it the BIA could not provide accurate account information.19

Back on the reservation, Cobell was trying to get the BIA to explain the discrepancies in monumentally flawed system. Even after she was dismissed for her inability to understand it, she didn’t give up. “I’d write and write and write,” she remembered. “One guy hadn’t paid in a year” for land he used. “He’d gotten away with all the oil on a lease for free.”20 She wrote letters for the tribal elders that came to ask her for help as well, finding yet more holes in the accounts. “By the time I got more and more into this, I knew the abuse was horrible. So how can you walk away from it? How could you feel like a person and walk away from the corruption?”21

Cobell started bringing her complaints to Washington. In the late 1980s, she testified in congressional hearings about the trust accounts. In the resulting 1992 report, “A Misplaced Trust,” Congress declared, “It is apparent that top officials at the Bureau of Indian Affairs have utterly failed to grasp the human impact of its financial management of the Indian trust fund. The Indian trust fund is more than balance sheets and accounting procedures. These moneys are crucial to the daily operations of native American tribes and a source of income to tens of thousands of native Americans.” Two years later, Congress passed the 1994 American Indian Trust Reform Act.22

President Clinton appointed Paul Homan as Special Trustee to oversee implementation of the Act. Homan was a bank president and CEO who had supervised trust operations of the Comptroller of the Currency, and had cleaned up several troubled banks. But in the trust accounts he found a chaos he had never imagined. Out of the 238,000 individual trusts his team located, 16,000 had no documents at all, and 118,000 were missing crucial papers. 50,000 didn’t even have addresses—meaning the money in the accounts never left the Treasury.23 The situation was an invitation to misuse. “It’s akin to leaving the vault door open,” Homan later said, “You leave it open and sooner or later it’s going to tempt somebody. If you don’t have records and you don’t have management, you don’t have much.” 24 Homan ultimately resigned, claiming Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt prevented him from completing the work demanded by the act.25

By 1996, Cobell had enough. The final straw was when Attorney General Janet Reno invited her to Washington to talk about the problem, but then refused to meet her and foisted her off on an aide. In 1989, the chair of the congressional oversight committee had introduced her to leading banking lawyer Dennis Gingold. Gingold knew nothing about the BIA (he later said he thought the meeting was about banking with India) and was shocked at the depth of the problem. She persuaded him to take it on. In 1996, having partnered with the Native American Rights Fund and four other representative plaintiffs, Cobell and Gingold filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of the hundreds of thousands of individual Indian money (IIM) account holders. Their complaint didn’t demand money, even though they estimated that the BIA owed the class members billions of dollars. They just wanted an accounting, for the BIA to say where there money was and what they had done with it.

Initially, even the Department of Interior’s lawyers were unprepared for the scope of the problem. Blithely promising to comply with discovery requests, the lawyers found that complying was no easy task. Documents were kept in garbage bags and disintegrating boxes; they had been destroyed by water and gnawed by rodents. Some, the defendants claimed, could not be produced because they might be contaminated with hantavirus, a deadly disease carried by mice and rats. Three years after the case began, the defendants hadn’t even produced the documents to reconcile the five individual plaintiffs’ accounts. 26

On December 21, 1999, after a six-week trial, the district court issued a scathing opinion:27 It would be difficult to find a more historically mismanaged federal program than the Individual Indian Money (IIM) trust. As the trustee admitted on the eve of trial, it cannot render an accurate accounting to the beneficiaries, contrary to a specific statutory mandate and the century-old obligation to do so. . . .

It is entirely possible that tens of thousands of IIM trust beneficiaries should be receiving different amounts of money–their own money–than they do today. Perhaps not. But no one can say, which is the crux of the problem.28

The court held that the defendants had egregiously failed to meet their fiduciary responsibility to provide account holders with accurate accountings and properly keep records for their accounts.

The court ordered the defendants to fulfill those duties, and provide the court with quarterly reports on their progress.29

In his conclusion, Judge Lamberth had written, “plaintiffs should take great satisfaction in the stunning victory that they have achieved today on behalf of the 300,000-plus Indian beneficiaries of the IIM trust.”30 When her lawyers called Cobell to deliver the news, she pulled her pickup truck to the side of the road and cried. 31 But the battle was far from over. The litigation dragged on for another ten years.

The case involved literally miles of documents, government projects costing tens of millions of dollars, and dozens of experts and private firms working for the United States. By 2008, there were 3,504 entries in the judicial docket for the case and the case had been before the Court of Appeals nine times. It was a huge job just raising the money necessary to keep the lawsuit going. Cobell had funded the initial litigation with a $75,000 grant and a $600,000 loan from the Otto Bremer Foundation.32 She put in her $310,000 MacArthur Foundation grant as well. The Lannan Foundation donated another $4.1 million.33 By the end, litigation had cost 11 million dollars— not including attorney fees—most of which Cobell raised from a variety of loans and grants.

But the lawsuit was just one of her projects. Cobell stepped down as director of the Blackfeet National Bank when it became the Native American Bank, but founded and became executive director of its non-profit arm, the Native American Community Development Corporation (NACDC).34 Through the NACDC, she consulted with tribes and small businesses to create sustainable economic plans, and created financial literacy programs, including a mini- bank program for elementary schools. Largely with financing from the bank, her Blackfeet community, though still poor, developed 200 new businesses, mostly with financing from the bank she founded. She organized an annual fundraising gala in East Glacier Park, using the funding to start a recycling program and other projects. She initiated the first tribal land trust program, the Blackfeet Land Trust, to protect 1,200 acres of crucial grizzly bear habitat. One reporter called her a “dream source,” the person to talk to about any new initiative. And in the middle of it all, in 2005, Cobell donated a kidney to her husband.

Work on the lawsuit was often less rewarding. Although the Blackfeet Nation honored her with warrior status in 2000, as the case dragged on she faced many challenges, some from tribal leaders and allotment holders themselves. In October 2004, the BIA withheld checks or information about allotments to the allotment owners, telling them (falsely) that it was a result of the Cobell litigation.35 For long periods, BIA and even Department of Interior websites were shut down completely after the court found that trust information was insecure and ordered the defendants to disconnect internet connections to that information. Many began to wonder if the suit was worth it, particularly as the government poured millions of federal dollars—dollars which might otherwise go to provide services directly to Indians—into accomplishing the accounting and defending the litigation. Some even started to say that Cobell was just in it to secure a big payoff for herself.

Meanwhile, District Judge Lamberth had become more and more frustrated with the defendants’ inaction. Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt was replaced by Secretary Gail Norton, and then Dirk Kempthorne, and the judge held each of them—as well as many other government officials and attorneys—in contempt, finding that they inexcusably failed to make progress toward compliance with their trust responsibilities, continued to destroy and fail to properly maintain records, and lied to the court about their progress. A Reagan appointee and native Texan who had been in charge of civil litigation for the United States for years before his his appointment, Lamberth was no bleeding heart liberal. But his extensive government experience had made him wise to the ways of government agencies as their attorneys. According to one attorney who knew him well, Lambert “was a master bureaucrat in the U.S. Attorney’s Office And as a judge, he hasn’t forgotten anything. He doesn’t just know where the bodies are buried, he knows how to bury the bodies.”36 He already had a reputation for impatience with government evasion, but in the trust litigation his frustration reached a new level.

Finally, Judge Lamberth went too far. In a 2005 decision, he ordered the defendants to include with any communication with the hundreds of thousands of class members a statement that all of the information about their accounts was unreliable. The decision included a bitter condemnation of the defendants:

After all these years, our government still treats Native American Indians as if they were somehow less than deserving of the respect that should be afforded to everyone in a society where all people are supposed to be equal.

[R]egardless of the motivations of the originators of the trust, one would expect, or at least hope, that the modern Interior department and its modern administrators would manage it in a way that reflects our modern understandings of how the government should treat people. Alas, our “modern” Interior department has time and again demonstrated that it is a dinosaur—the morally and culturally oblivious hand-me-down of a disgracefully racist and imperialist government that should have been buried a century ago, the last pathetic outpost of the indifference and anglocentrism we thought we had left behind.37

The defendants appealed the order, and asked for Judge Lamberth to be removed from the case. Citing the language of the district court opinion, as well as the numerous appellate reversals of contempt findings and other orders, the Court of Appeals agreed. This was one of the rare cases, it found, where the judge’s “professed hostility” was “so extreme as to display clear inability to render fair judgment.”38 Emphasizing that the defendants remained in breach of their trust responsibilities, with no remedy in sight, the Court of Appeals ordered the case assigned to a new judge. For Cobell, “That was a low point. We knew it would be hard to get a new judge up to speed. The government has all the money in the world, but we don’t have deep pockets.”39

In 2008, Judge James Robertson, the new trial judge, found that despite the millions of dollars spent and proposed to be spent to provide an accounting to Individual Indian Money account owners, their plans still fell short of fulfilling their trust responsibility. Providing an accurate and complete accounting would cost as much as 12 billion dollars, and still might not be possible given the gaps in the document record. As the accounts themselves were only worth some two billion dollars, a complete accounting would be, he wrote, “nuts.” That being the case, there had to be some other remedy for the defendants’ failures.40

A few months later, Judge Robertson announced what the remedy should be: the defendants would pay the plaintiffs 455 million dollars. Although this covered the money the defendants said was missing from the trust fund, it didn’t include any of the money lost due to mishandling or withholding of funds. The plaintiffs believed that figure to be tens of billions, while some of the government’s own documents suggested it was as much as three billion dollars.41 In 2009, the Court of Appeals reversed the district court’s judgment, holding that it failed to adequately hold the United States to its trust responsibilities.42

Finally, December 2009, the plaintiffs and new Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar announced a settlement. The United States would distribute $1.5 billion among the plaintiffs to compensate for mismanagement of their accounts, provide $1.9 billion dollars to purchase fractionated lands for consolidation in the tribe, and devote an addition $60 million for higher education scholarships. Cobell felt that the plaintiffs were due much more, but that they needed to accept the settlement. “Time takes a toll,” she said, “especially on elders living in abject poverty. Many of them died as we continued to struggle to settle this suit. Many more would not survive long to see a financial gain, if we had not settled now.”43

Even then, her struggle was not over. Congress still had to appropriate the money to fund the settlement. Now 64, Cobell was tireless in pushing for the appropriation before class beneficiaries could die. In April 2010, she fractured her occipital bone after she fainted and fell on the sidewalk after a sleepless night followed by a day rushing from meeting to meeting with congressional leaders.44 In November, when the Senate blocked the deal yet again, she told reporters, “We’ve lost three people in the last week here [on the Blackfeet Reservation] who were beneficiaries to this settlement, and it hurts.”45

In December 2010, almost a year after the initial agreement, the bill passed the House. On December 8, 2010, Cobell returned to Washington for the signing ceremony. President Obama credited her by name:

[This case] began when Elouise Cobell — who’s here today — charged the Interior Department with failing to account for tens of billions of dollars that they were supposed to collect on behalf of more than 300,000 of her fellow Native Americans.

Elouise’s argument was simple: The government, as a trustee of Indian funds, should be able to account for how it handles that money. And now, after 14 years of litigation, it’s finally time to address the way that Native Americans were treated by their government. It’s finally time to make things right.

Cobell called the signing “breathtaking” and said the settlement “paves the way for a brighter and better relationship with government.” Her son Turk was more subdued. “We’re obviously proud of her but we’re glad it’s over. My mother is tremendously relentless when it comes to doing what she believes is right. Maybe now she can finally enjoy a normal life again and get something she hasn’t had: rest.”

***

Cobell didn’t get that rest. Six months after the signing ceremony, she went to the Mayo Clinic for an operation for cancer. On October 16, 2011, the cancer killed her. The day before her funeral, the local radio station played her favorite singer, Elvis Presley, all day in her honor. On October 22, thousands gathered in the Browning High School Gym to mourn and remember her. The Crazy Dog Society together with uniformed Blackfeet veterans had escorted the casket to the high school the night before, stopping four times to pray and sing for the lost Blackfeet warrior. A line of cars traveled the thirty miles to the family ranch, where she was buried amid Catholic and Blackfeet prayers. After her death, a small piece of paper remained taped to her office computer. It read:

***

Further Reading:

Cobell v. Norton, 240 F.3d 1081 (D.C. Cir. 2001) Cobell v. Babbitt, 91 F. Supp. 2d 1 (D.D.C. 1999)

Cobell v. Kempthorne, 532 F. Supp. 2d 37 (D.D.C. 2008)

Misplaced Trust: Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Mismanagement of the Indian Trust Fund, H. R. No. 102-499 at 9 (1992)

Pauline Arrillaga, Elouise Cobell, A Blackfeet Woman Takes on the Government: And Wins, Ms. Dec. 1, 2000

J. Michael Kennedy, Truth and Consequences on the Reservation, Los Angeles Times, July 7, 2002

Mark Ratledge, The Burial of Elouise Cobell, High Country News, Oct. 28, 2011 Louise Sahagun, Tangled Trust Earns Wrath of Native Americans, L.A. Times, Nov. 10, 1996

Julia Whitty, Accounting coup: when banker Elouise Cobell added up the Indian trust money lost, looted, and mismanaged by the U.S. government, the tab came to $176 billion. Now she’s here to collect, Mother Jones, Jan. 29, 2005

***

Notes:

1 Louise Sahagun, Tangled Trust Earns Wrath of Native Americans, L.A. Times, Nov. 10, 1996.

2 J. Michael Kennedy, Truth and Consequences on the Reservation, Los Angeles Times, July 7, 2002.

3 Pauline Arrillaga, Indian Woman Steps in to Call U.S. to Account, Seattle Times, Nov. 7, 1999.

4 Pauline Arrillaga, Elouise Cobell, A Blackfeet Woman Takes on the Government: And Wins, Ms. Dec. 1, 2000.

5 Pauline Arrillaga, Indian Woman Steps in to Call U.S. to Account, Seattle Times, Nov. 7, 1999.

6 J. Michael Kennedy, Truth and Consequences on the Reservation, Los Angeles Times, July 7, 2002

7 Julia Whitty, Accounting coup: when banker Elouise Cobell added up the Indian trust money lost, looted, and mismanaged by the U.S. government, the tab came to $176 billion. Now she’s here to collect, Mother Jones, Jan. 29, 2005.

8 Daniel McQuillen, Blackfeet Banker’s Grant Rewards Genius for Getting Things Done, National Banker, June 24, 1997.

9 http://www.nabna.com/about.shtml.

10 Julia Whitty, Accounting coup: when banker Elouise Cobell added up the Indian trust money lost, looted, and mismanaged by the U.S. government, the tab came to $176 billion. Now she’s here to collect, Mother Jones, Jan. 29, 2005.

11 Lonnae O’Neal Parker, Out of the Blue Comes Green; 23 Artists, Authors, Academics and Activists are Surprised with MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grants, June 17, 1997.

12 Lonnae O’Neal Parker, Out of the Blue Comes Green; 23 Artists, Authors, Academics and Activists are Surprised with MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grants, June 17, 1997.

13 Misplaced Trust: Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Mismanagement of the Indian Trust Fund, H. R. No. 102-499 at 9 (1992).

14 Misplaced Trust: Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Mismanagement of the Indian Trust Fund, H. R. No. 102-499 at 9 (1992).

15 Cobell v. Babbitt, 91 F. Supp. 2d 1, 9 (D.D.C. 1999).

16 78 Cong. Rec. 11728 (1934) (Rep. Edgar Howard).

17 Misplaced Trust: Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Mismanagement of the Indian Trust Fund, H. R. No. 102-499 at 9 (1992).

18 Peter Maas, The Broken Promise, Parade Magazine, Sept. 9, 2001.

19 Misplaced Trust: Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Mismanagement of the Indian Trust Fund, H. R. No. 102-499 at 9 (1992).

20 J. Michael Kennedy, Truth and Consequences on the Reservation, Los Angeles Times, July 7, 2002.

21 Matt Volz, Blackfeet woman close to victory in 14 year fight, Deseret News, May 23, 2010

22 PL 103–412, October 25, 1994, 108 Stat 4239.

23 J. Michael Kennedy, Truth and Consequences on the Reservation, Los Angeles Times, July 7, 2002.

24 Id.

25 Peter Maas, The Broken Promise, Parade Magazine, Sept. 9, 2001.

26 Cobell v. Babbitt, 37 F. Supp. 2d 6 (D.D.C. 1999).

27 Cobell v. Babbitt, 91 F. Supp. 2d 1 (D.D.C. 1999).

28 91 F. Supp. 2d at 6.

29 Id. at 54-57.

30 Id. at 57. Although the defendants appealed the order, in 2001 the Court of Appeals comprehensively upheld it. Cobell v. Norton, 240 F.3d 1081 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

31 Pauline Arrillaga, Indian Woman Steps in to Call U.S. to Account, Seattle Times, Nov. 7, 1999.

32 Nancy Traver, Activist’s Suit Tackles Goliath, Chicago Tribune, Oct. 9, 2002.

33 Id.

34 Julia Whitty, Accounting coup: when banker Elouise Cobell added up the Indian trust money lost, looted, and mismanaged by the U.S. government, the tab came to $176 billion. Now she’s here to collect, Mother Jones, Jan. 29, 2005.

35 Cobell v. Norton, 29 F.R.D. 5, 10 (D.D.C. 2005).

36 Jonathan Groner, A Scramble for Cover in Indian Case: Officials tap private counsel to avoid district judge’s wrath, Legal Times (Nov. 20, 2001).

37 Cobell v. Norton, 29 F.R.D. 5, 7 (D.D.C. 2005).

38 Cobell v. Kempthorne, 455 F.3d 317 (D.C. Cir. 2006) (quoting Liteky v. United States, 510 U.S. 540, 551 (1994).

39 Blackfeet Woman Who Led Indian Land Settlement Fight Dies at 65, Tulsa World, October 18, 2011.

40 Cobell v. Kempthorne, 532 F. Supp. 2d 37 (D.D.C. 2008).

41 Cobell v. Kempthorne, 569 F. Supp. 2d 223, 226 (D.D.C. 2008).

42 Cobell v. Salazar, 573 F.3d 808 (D.C. Cir. 2009).

43 Valerie Nelson, Elouise Cobell: 1945-2011, L.A. Times, Oct. 18, 2011.

44 Matt Volz, Blackfeet woman close to victory in 14 year fight, Deseret News, May 23, 2010

45 Blackfeet Woman Who Led Indian Land Settlement Fight Dies at 65, Tulsa World, October 18, 2011.

46 Mark Ratledge, The Burial of Elouise Cobell, High Country News, Oct. 28, 2011

Contact Us At Your Convenience

The Cobell Scholarship Team is available to address any questions or concerns regarding the scholarship process or other related inquiries. Simply complete and submit the form below.

Indigenous Education, Inc.

The Cobell Scholarship

2155 Louisiana Blvd NE Suite 10100

Albuquerque NM 87110

The Cobell Scholarship

2155 Louisiana Blvd NE Suite 10100

Albuquerque NM 87110